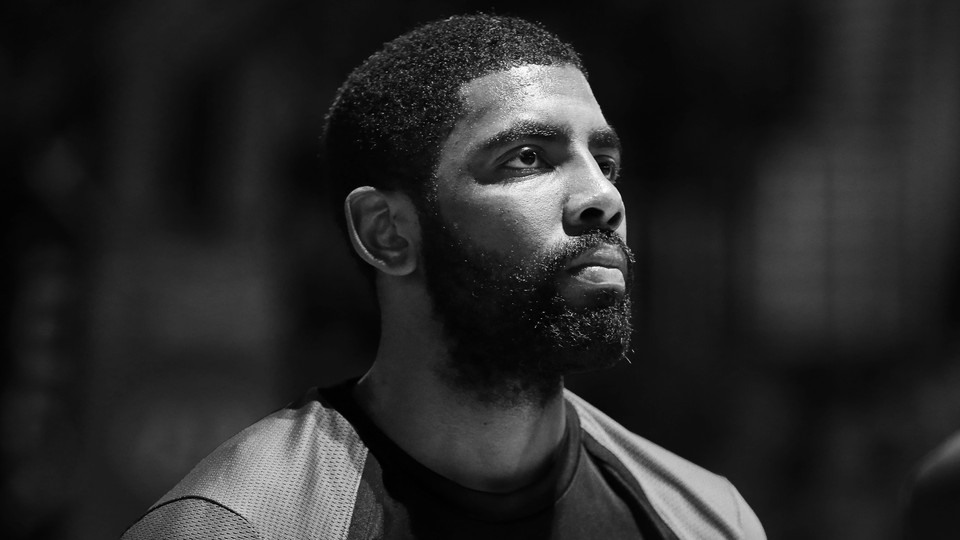

What Does Kyrie Irving See in Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories?

The NBA star joins a troubling club.

Kyrie Irving, the Brooklyn Nets’ superstar point guard, is as skilled at deflection as he is at putting together spectacular finishes around the basket. On Saturday, after his team’s 125–116 loss to the Indiana Pacers, a reporter vigorously questioned Irving about why he used his Twitter account to promote Hebrews to Negroes: Wake Up Black America, a 2018 film that contains a host of anti-Semitic themes.

“It’s on Amazon, public platform,” Irving said of his decision to post a link to the purported documentary, which was adapted from a book of the same name. “Whether you want to go watch it or not is up to you. There’s things being posted every day. I’m no different than the next human being, so don’t treat me any different. You guys come in here and make up this powerful influence that I have … [and say], ‘You cannot post that.’ Why not? Why not?” He went on to suggest that he hadn’t expressed hatred for anyone, and he appeared to link the controversy—without explaining the connection—to his own experience of “living as a free Black man here in America, knowing the historical complexities for me to get here.”

In reality, Irving has joined a troubling club of high-profile Black male celebrities—also including the rapper Kanye West—who have stubbornly embraced conspiracy theories, particularly anti-Semitic ones, under the pretext of seeking a deeper truth about their own origins.

Black men are not the primary drivers of anti-Semitism in the United States. But polls suggest that they do feel more disenfranchised and disengaged from the political process than most other demographic groups do. Black men have historically been villainized, and often do not feel seen and certainly not heard or respected.

I can’t help but wonder about a correlation between that sentiment and the anti-Semitic conspiracy theories now percolating even among highly successful artists and athletes—theories rooted in the idea that the greatness of Black men is being hidden or stolen from them. There is nothing wrong with Black men examining their roots to better understand their place in history or in the world, but it’s hard to believe that this can’t be done without advancing ideas that denigrate others.

Irving has since deleted the tweet in question, but he doesn’t seem to realize that he isn’t just a garden-variety internet poster. The three-hour film that he amplified to his millions of followers is repugnant. At one point, the film cites Henry Ford’s four-volume book The International Jew. (The first volume is subtitled The World’s Foremost Problem.) A quick history lesson: The legendary automaker’s disdain for Jews was so intense that even Adolf Hitler praised him for it in Mein Kampf. Even more chilling, the documentary also claims that Jews have used five major falsehoods to “conceal their nature and protect their status and power.” One alleged falsehood is that 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust.

Irving later insisted that his being labeled anti-Semitic was “not justified.” I’m not sure which definition of anti-Semitic Irving is working with, but how else could someone characterize his support for a film that treats the Holocaust as an exaggeration or a falsehood?

Irving says that he embraces and strives to learn from all walks of life and religions. If so, part of his education should include being conscious and understanding of the painful histories that have caused those communities harm.

Nevertheless, Black Americans’ suffering has not automatically sensitized us to other forms of prejudice, and other Black men have trotted down Irving’s path. In 2020, I wrote about the NFL star wide receiver DeSean Jackson, who posted a screenshot on Instagram of a fake Hitler quote declaring that white Jews will “blackmail America” and that “Negroes are the real Children of Israel.”

More recently, West—who has changed his legal name to Ye—has been all over the news for weeks because of his anti-Semitic opinions. In a now deleted tweet, he promised last month to go “death con 3 on Jewish people.” When he made an appearance last month on the popular hip-hop-oriented podcast Drink Champs, he said that “Jewish people have owned the Black voice.” He also said that Black people couldn’t be anti-Semitic because they’re Jewish at their roots.

He has since retracted his statements and proclaimed that he didn’t mean any harm, but that was only after he lost endorsement deals with prominent advertisers including Balenciaga, Adidas, and Foot Locker. (That his anti-Semitic comments have cost him lucrative gigs but his disparagement of George Floyd has not has become the source of a separate controversy.)

In September, Irving posted an old video, from the conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, discussing secret societies that are supposedly part of a “new world order.” Jones, of course, was recently ordered to pay nearly $1 billion to the families of the Sandy Hook Elementary–shooting victims for peddling the inexcusable conspiracy theory that the shooting was a myth and the victims were paid actors. Jones claimed this hoax was part of a larger plot to institute gun control.

The Nets star has publicly defended his actions and maintained that he didn’t support Jones’s reprehensible campaign against the surviving Sandy Hook families; he just felt that Jones was right about secret societies. How Irving could place any trust in someone who maliciously lied about the murder of more than two dozen people, including 20 children, is simply bewildering.

The Nets’ owner, Joe Tsai, has admonished Irving for his recent actions, and some commentators have called for Irving’s suspension. Punitive action aside, Irving has become far better known for his contrarian viewpoints than for his basketball brilliance. This is the same player who missed Brooklyn’s home games last season and turned down a $100 million contract because he refused to get vaccinated against the coronavirus. And he seems to feel that couching ideas in shallow intellectualism, or just claiming to be misunderstood, is enough to shield him from any real criticism. When challenged about something he believes, Irving just digs in—no matter the consequences.